The Good Society is the home of my day-to-day writing about how we can shape a better world together.

A detail from Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Renaissance fresco The Allegory of Good and Bad Government

Stuff: Time to shine a light on waste

The circular economy is a concept we’ll all be hearing more about in future.

Read the original article on Stuff

The Surrealists thought landfills were a society’s subconscious. In dreams, the experiences we have tried to suppress come bubbling up from the depths. In rubbish dumps, society attempts to cast things off and forget the costs of its own pollution; but still, like a nightmare, the garbage rises.

Sometimes landfills explode, strewing trailer-loads of rubbish across pristine coasts and waterways, as happened in 2019 near the Fox River. And the wider problem has begun to press itself onto our conscious mind.

According to the annual Kantar opinion poll, no fewer than three pollution-related issues – plastic build-up, excess waste, and over-packaging – are in the public’s top 10 concerns. We’re slowly acknowledging that we are, quite simply, rubbish at rubbish.

New Zealand generates 781kg of municipal waste per person; only two developed countries have a worse record. Just one-quarter of our waste is recycled or otherwise repurposed. Some 13 million tonnes annually – 760 Interislander ferries filled to the brim – is dumped, a colossal squandering of resources that have been ripped from the earth, used perhaps once or twice, and thrown away.

The results can be seen on beaches littered with coffee-cup lids, plastic bags and bin liners. Rubbish pollutes our shores, leaches into the soil, chokes turtles and dolphins.

And if the end state of these objects is bad, the start is no better: around half the world’s climate-change-inducing emissions are generated in making things, the Ellen Macarthur Foundation estimates. We continuously breach our planet’s boundaries – and the things we consume play a large part in that grim story.

Recycling, the most commonly touted solution, is useful, but won’t by itself save us. Don’t get me wrong: I love recycling. It’s in the blood: my grandmother, Kae Miller, spent part of the 1970s living on the Porirua tip in protest against the lack of recycling. But it’s still a process in which energy and materials are lost.

We need to embrace the wider suite of measures wrapped up in what’s known as the circular economy, a concept set to define the coming decades. It valorises products that are durable and reusable, objects with a life after their initial purpose, items that can circulate multiple times. It is a recipe for simply bringing less stuff into existence.

We can embrace the circular economy as individuals, and in families and communities, by finding sources of pleasure that don’t involve buying things. Where we do have to buy them, and where budgets allow, we can choose better made, more durable objects. (Or renovated ones: I’m typing this column on a refurbished ex-business laptop that runs beautifully.)

We’ve all acclimatised to taking our own shopping bags to the supermarket. In future we’ll carry more such receptacles: Keep Cups for coffee, Tupperware for takeaways. It’s not just things themselves that should be re-used but also their packaging.

We must also, however, act collectively to change the laws and regulations that shape our choices, so that those rules make it easy for us to do the right thing while punishing people who would keep exploiting the planet.

The first step is to place most responsibility where it lies best: with the manufacturers. They need to be made product “stewards”, responsible for an item’s life from conception to disposal.

Too many products are a fused plastic shell, the mechanical parts hidden inside, inaccessible to a would-be repairer. In response, several states have introduced right-to-repair schemes, forcing companies to make easily fixable products, stock spare parts for up to a decade, and stop requiring consumers to get items repaired at expensive, company-linked shops.

People are still unlikely to get their toaster fixed, though, if it’s cheaper to buy a new one. And that points to a wider problem: our economic system doesn’t properly recognise the value in extending products’ lives, nor the damage done by unnecessary waste.

One solution is to change the price of those actions. Some Austrian cities hand out vouchers that give individuals 50% off the cost of fixing goods (up to a few hundred dollars). The Swedes provide tax breaks for repairs.

Such initiatives could be funded by increasing tip fees and levies on manufacturers. We could also reintroduce container deposit schemes – the old “20c for every bottle you return” initiatives that New Zealand once employed and which have slashed plastic-vessel pollution in other countries.

In this new world, polluters would start to bear the social and environmental costs of their actions, while firms would see more financial value in re-using items. Jobs making stuff would be replaced with jobs repairing stuff.

The Ministry for the Environment, which has already proposed several circular-economy initiatives, needs to keep its resolve, and make them reality. For too long, waste has been near-invisible. Bringing it back into the light may prove to be one of the most revolutionary economic changes we could have ever made.

Prospect: Wealth taxes work. Just look at Argentina

Wealth taxes are increasingly popular with the public, and governments now have more tools to enforce them.

Read the original on the Prospect site

Imagine if £450bn of previously hidden assets were suddenly disclosed by Britain’s wealthiest citizens, and became subject to tax. If that seems implausible, it’s simply what has happened in Argentina in recent years.

In 2016, the Argentine government, which has long levied an annual wealth tax on its most prosperous inhabitants, announced an amnesty: if citizens declared hitherto undisclosed wealth, they would be spared prosecution for past unpaid tax. The results were spectacular. Assets worth 21 per cent of Argentina’s GDP, the equivalent of £450bn in Britain, were declared. Revenues from the wealth tax doubled.

The Argentine experience is part of a wider trend that suggests taxing wealth “is definitely more possible today than it was five years ago”, says Juliana Londoño-Vélez of the University of California. Until recently, however, wealth taxes had been on a long, slow decline, their demise hastened by conservatives who successfully painted such levies as an attack on entrepreneurs and a disincentive to saving. Although in the 1990s a dozen European countries levied wealth taxes, that number has since shrunk to three: Norway, Switzerland and Spain. Most developed countries now seek to tax only limited forms of wealth, such as property.

Awareness of growing economic disparities, however, combined with governments’ need for new sources of revenue, has put wealth taxation back on the table. And it is increasingly popular. In September last year, YouGov polling found public support for taxing wealth more, and income less, in every one of the 11 countries surveyed, including the UK, the US, Australia and Canada. And just last week, the same firm’s polling showed three-quarters of Britons back an annual levy of 2 per cent on wealth over £5 million (clear of debts). Under this tax, someone worth £15m would pay £200,000 a year (2 per cent of the £10m they hold over the £5 million threshold).

Some doubt whether the very wealthy, adept at avoiding tax through complex offshore arrangements, could be made to pay such sums. Londoño-Vélez’s research, however, suggests the net is closing, albeit slowly. Argentina’s amnesty was successful in part because countries are increasingly signing treaties which enable them to share bank data on the assets that citizens of one nation hold in the other. In this instance, the US and Swiss tax authorities agreed to start telling their Argentine counterpart what financial assets Argentines held in their banks. The Panama Papers, an explosive leak of tax-haven data in 2016, drastically increased official disclosures from wealthy Argentines who had effectively already been outed.

Governments now have more tools to enforce wealth taxation, Londoño-Vélez says. “It’s an area where there’s a lot of developments happening as we speak.” Tax havens remain “a huge threat”. But, she adds, “I can see where the loopholes are, and I can see how policy can progressively close them.”

The need to tackle economic disparities adds weight to the wealth-tax cause. Wealth is generally twice as concentrated as income (itself very unequally distributed). Recent Oxfam research suggests the world’s billionaires have taken a striking two-thirds of all the new wealth generated since the pandemic. And the world has been more attentive to such questions ever since the publication of Thomas Piketty’s 2014 blockbuster Capital in the Twenty-First Century, which argued that wealth taxation could break up plutocratic concentrations of economic power.

It could also bolster the integrity of the wider tax system. Tracking flows of interest, rent and dividends shows that much income is generated from wealth. And when people are forced to reveal more of the latter, they are also forced to reveal more of the former. Following Colombia’s tax amnesty, the wealthy disclosed over US$12bn of previously hidden assets – but also paid 39 per cent more income tax. A wealth levy, Londoño-Vélez argues, has “a very positive effect on the income tax system”.

Piketty, meanwhile, believes European countries abandoned wealth taxes not because they were inherently flawed, but because the taxes had—under political pressure—become riddled with so many exemptions that they generated little revenue. In certain cases, they also caught the middle classes—something that would be avoided with, say, a tax cutting in at £5 million net worth.

Despite the positive polling, British politicians—especially on the left—may fear the expressed public support is soft, and would melt under the blowtorch of Conservative claims about taxing “wealth creators” and frightening away investment. But Labour could very easily point to Switzerland, which has long had an annual wealth tax that generates roughly 1 per cent of GDP, the equivalent of nearly £21bn a year in Britain.

Such levies have evidently not caused the Swiss state to be suddenly abandoned by its billionaires. Londoño-Vélez, meanwhile, declares herself “optimistic” about the prospects for wealth taxation. “If countries like Colombia and Argentina … have a wealth tax, and have their citizens report their assets,” she says, “I don’t see why it can’t be done in other countries.”

Stuff: On education, we know what Hipkins dislikes better than what he likes

For all the good intentions, little of the reform he has introduced would survive a change in government.

Read the original on Stuff

Policies, promises, compromises: if you want to know what Chris Hipkins might do as this country’s leader, it’s all there in his record as minister of education, the post he held from 2017 until this week.

Sure, he loves DIY, sausage rolls and Cossie Clubs. But to understand the ideas he’d implement, we should examine his achievements, or lack thereof, to date. For his approach to schooling – to take just one part of his legacy – is a microcosm of this Government’s record, where ambition has outstripped actual change.

Of course, some problems that bedevil New Zealand education – like the slow-motion collapse of our global rankings in literacy and numeracy – are long-standing and driven partly by forces of poverty and discrimination that are well beyond Hipkins’ control.

He’s had to battle obstacles ranging from Winston Peters, in his first term, to Covid, in his second. And he’s done repair work. Cathy Wylie, a respected education researcher, points out that under National, the ministry’s curriculum section “was pretty well disbanded”. That hollowing-out of capacity had to be fixed.

Hipkins always knew what he didn’t like. National Standards and charter schools were both swiftly – and rightly – dispatched.

What he does like can be harder to discern. Clarence Beeby, the legendary post-war director of education, once described schooling’s mission thus: “All persons, whatever their ability, rich or poor, whether they live in town or country, have a right as citizens to a free education of the kind for which they are best fitted and to the fullest extent of their powers.” It’s safe to say nothing so clear or inspiring has emerged from the ministry in recent years.

And the two big wins on Hipkins’ watch – the replacement of the flawed decile system with an “equity index” for funding poorer schools, and the new history curriculum – owe much to his predecessors as education minister (Hekia Parata) and prime minister (Jacinda Ardern).

He has, however, been willing to address deep-seated, oft-neglected issues, something Wylie believes made him “a very ambitious minister of education, one of the most ambitious we’ve had, probably”.

The curriculum, the structure of NCEA, vocational education, school property, early learning: all have been put up for grabs. The problem is that, instead of decisive action, this has often produced a morass of reviews that move very slowly, all tangled up in each other like badly cast fishing lines. Consultancy spending has ballooned.

Some planned policies, meanwhile, are actively harmful. Confronting the decline in literacy and numeracy, Hipkins could have focused on the upstream sources of the issue, but is instead piloting compulsory tests that vast numbers of 15-year-olds will flunk, derailing their education.

Other moves have been more positive. Wylie was a member of the 2019 review of Tomorrow’s Schools, which exposed the system’s big flaw: the way that competition isolates schools from each other, leaving struggling establishments to their fate and making it harder for successful strategies to be shared.

The review’s solution – greater co-operation between, and support for, schools – is slowly being adopted. The ministry has been restructured to help it interact better with teachers and schools. A new education service agency, Te Mahau, will assist those who are struggling. Leadership advisers have been appointed to support principals, and the ministry has removed schools’ ability to manipulate their zones and steal others’ (well-off) pupils.

The foundations of reform are being laid. But how many will endure? In my judgment, only a few changes have built enough momentum and popular support not to be overturned if Hipkins loses October’s election.

Transformational moments have come and gone. When Covid struck, the ministry scrambled to get computers into low-income homes, to aid remote learning. But this never developed – as it should have – into a national mission to ensure every home had the devices and the broadband needed to eradicate the digital divide.

A final anecdote is telling. When the Tomorrow’s Schools reviewers got underway, Hipkins asked them to speak to other political parties, including National and ACT, to test their ideas. “He wanted something that was robust and defensible, and likely to get support,” Wylie says.

Though sometimes labelled a “tribal” politician, Hipkins is, ultimately, a pragmatist, she adds. “He does his homework and he asks good questions... He’s unlikely to come out of left field with something that hasn’t been tested or discussed well. He’s not someone who would have random enthusiasms.”

So there you have it. Collective values and solid analysis, but in the service of pragmatism; greater clarity on what is opposed than what is supported; good intentions that get bogged down in reviews; foundations laid but with little guarantee they’ll endure; Covid opportunities passed up: as it is with this Government, so has it been in education.

Don’t expect too much new from prime minister Hipkins, in short. The singer changes but the song remains the same.

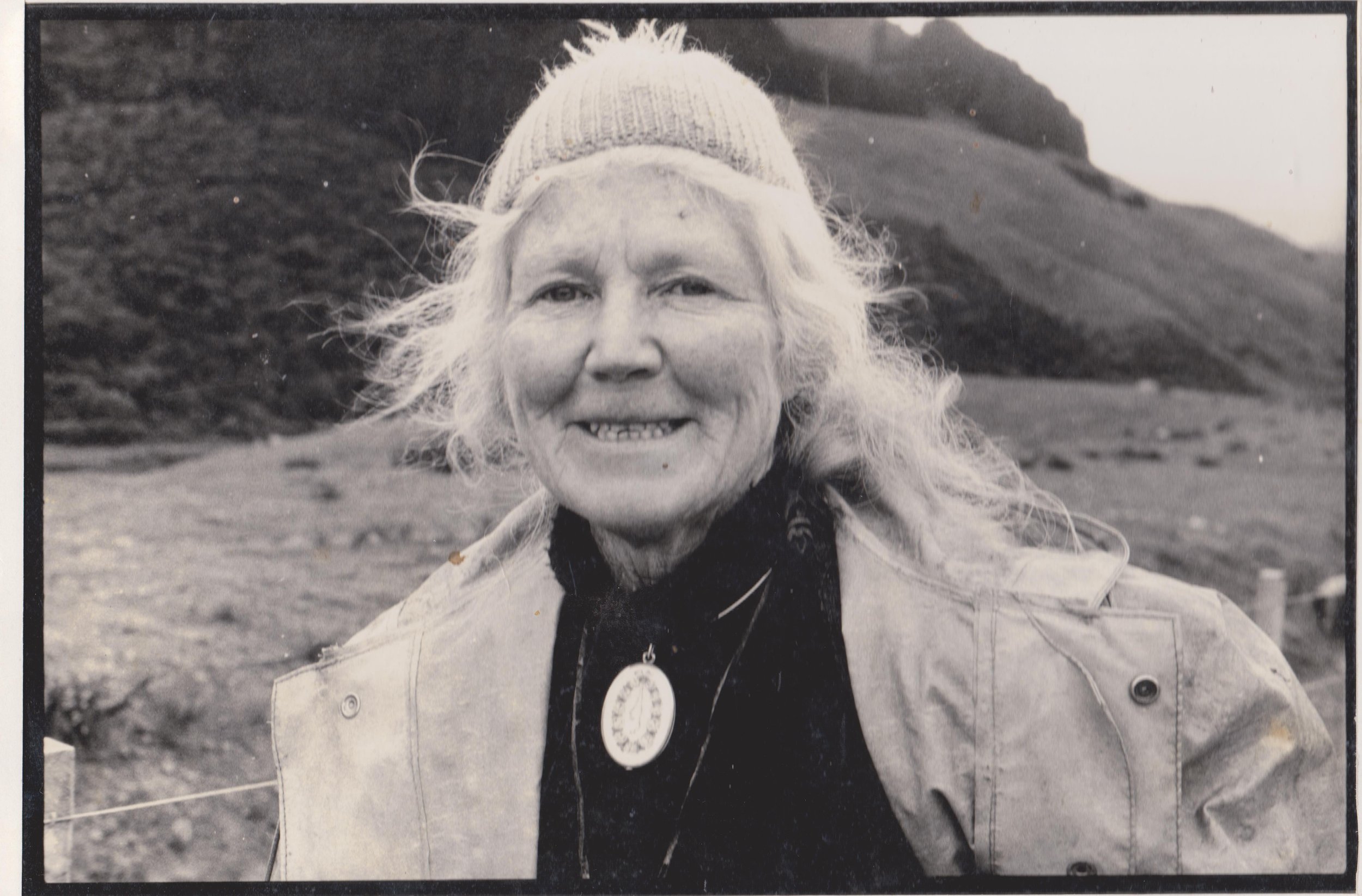

Kae Miller

Two photographs of my grandmother, a pioneering campaigner.

Below are two photographs of my maternal grandmother Kae Miller, a pioneering conservationist, peace advocate and mental health activist. Both photos are released under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/.

Stuff: Is the electorate in the mood for radical changes?

Incrementalism, radical or not, has ruled the roost. But the electorate might finally want something else.

Read the original on Stuff

“In politics,” the US president John Adams once wrote, “the middle way is none at all.”

But don’t tell that to politicians in New Zealand, where the middle way has been the only path trodden for decades now. Helen Clark, John Key, Bill English and Jacinda Ardern have all eschewed sweeping change.

Not that political life has been preserved in aspic: Clark (and her deputy Michael Cullen) gave us Working for Families, KiwiSaver and the Super Fund; Key part-privatised state energy companies and seeded charter schools; and Ardern’s governments have passed the Zero Carbon Act and raised benefits by $100 a week.

None of this, though, has radically changed this country, or fixed our long-standing deficiencies: elevated levels of poverty and inequality; poor productivity and low investment in R&D; underfunded public services; polluted rivers and lakes; extremely high greenhouse-gas emissions; appallingly expensive, cold and mouldy homes; and a ranking as just about the worst developed country in which to raise a child.

Some commentators blame this on MMP: its coalition governments, they argue, tend to hug the centre and block the radical change New Zealand needs.

But if a radical-change constituency had existed, politicians would have indulged it. I suspect it simply hasn’t been there.

This may reflect the lingering trauma of the 1980s, when finance minister Roger Douglas deliberately and undemocratically acted at breakneck pace, so that opponents had no time to respond.

Clearly the public has been content with political caution. Even after nine years of the last National government, 60% of New Zealanders said the country was on the right track. They weren’t demanding major change.

Labour’s response, at least rhetorically, has been to govern based on what Education Minister Chris Hipkins once told me was “radical incrementalism”: small steps towards a clearly stated and transformative goal.

This he distinguished from both the “crash-through” change of the 1980s and the “muddling-through” of recent governments unwilling to spell out their real goals lest it frighten the horses.

The theory of change – to the extent there was one – held that if people liked a small initial step, they would be “warmed up” to accept a bigger one. Where, though, has this really worked?

Perhaps with benefit increases, which the Government has cunningly made in increments of $20 a week here and there, profoundly changing beneficiaries’ incomes without much controversy. Even here, though, reform has fallen far short of the transformative vision of the 2019 Welfare Expert Advisory Group.

Fair Pay Agreements and social unemployment insurance would, if implemented, be modestly radical – but their fate hinges on the election, and they haven’t obviously been part of an incremental plan.

Elsewhere, the Zero Carbon Act has set the scene for the $4.5 billion Climate Emergency Response Fund, incrementally reshaping environmental politics, but concrete action remains lacking. And although Three Waters represents a gradual ramping-up of co-governance, it has – famously – not been well-received.

I think radical incrementalism has largely been a bust, for two reasons. First, it’s not clear that most ministers had a roadmap to a truly radical destination – or even wanted one.

Second, the theory of change has a clear flaw. Small initial steps don’t always warm people up to accept something bigger: often they can, despite their ostensibly humble ambitions, spark a massive political fracas; and with supporters exhausted, and opponents’ backs up, ministers may become less likely to step up the pace. Incrementalism can burn off, not build, political capital.

And here’s the killer irony: well before Hipkins started talking about radical incrementalism, Bill English was describing his government’s approach as “incremental radicalism”. Same house, slightly different paint colour.

But might incrementalism be junked this year? The above-mentioned right-track indicator fell sharply in 2022, as frustration over Covid and the cost-of-living crisis coalesced. In November a record-high 55% of Kiwis said the country was on the wrong track.

Having abandoned its internationally unusual positivity, New Zealand’s political mood is now closer to that of other developed countries – many of which have been roiled by populist revolts.

Commentator Matthew Hooton says Auckland polling reveals an “incredibly angry” electorate.

Meanwhile, we face what you might call a sidecar election.

On current polling, we’d have an extremely rare result in which the two flanking parties, ACT and the Greens, got around 10% each, while the two majors, Labour and National, got under 40%.

Sidecars like ACT and the Greens don’t have to deal with the nervous median voter. But if they keep polling well, one or the other could win unprecedentedly large concessions from their centrist big sibling.

The right is best placed, of course, to capitalise on the souring of the public mood. But it’s not inconceivable that the left could, too.

Either way, the age of small changes – of radical incrementalism and incremental radicalism – might be coming to a close.

Stuff: A brief history of the many times I changed my mind

We should all be readier to admit instances when we were wrong. Here’s a few of mine.

Read the original on Stuff

A new year approaches, and so I start to think – as I’m sure everyone does at this time – about the philosopher Hannah Arendt, a noted analyst of totalitarianism but also of political life in general.

Arendt believed that the human capacity for change derived from our consciousness of the novelty of our own life: “Since we all come into the world by virtue of birth, as newcomers and beginnings, we are able to start something new.”

This capacity for self-renewal is on display every time that, in response to new facts or stronger arguments, we change our mind. Each alteration is a new dawn.

But such shifts are under-valued today. In a seemingly chaotic era, many people seek comfort in a rigid certainty, dividing the world into good and bad. Debate becomes an opportunity to win, not to listen.

Columnists, who often feel they must have Correct Opinions if they are to justify their status, can find it hard to admit they’ve changed their mind. It creates a vulnerability. But what better way to model good public discussion? And what better time to do it than the new year?

Here, then, in the spirit of personal and public renewal, is a brief history of various things I have previously got wrong.

Marijuana legalisation

Strange to say, as a young man I was sceptical about legalising weed, partly because I bought the ‘’gateway drug’’ argument and partly because I believed that cannabis use caused psychosis. I now think the harms of our current approach outweigh any possible negatives from legalisation, and that some underlying third factor probably causes both dope-smoking and psychosis.

Mixed-tenure neighbourhoods

I once believed ardently that state-housing redevelopments should incorporate a large number of private rentals and owner-occupied homes, to stop them becoming ghettos. Then I read an evidence review that suggested mixed-tenure neighbourhoods, as they are called, often fail. The now-outnumbered state-house tenants feel marginalised, wealthier families dominate the residents’ associations, and local stores begin stocking more expensive products. Although I haven’t turned 180 degrees on this issue, I now mostly think that if there are problems with concentrated poverty, the issue is the poverty, not the concentration, and that we should fix the former.

The King Country

Embarrassing though it is to admit, I was well into my 30s before I discovered this area was named after the second Māori King, Tāwhiao, and not, as I had always assumed, one of the British monarchs. My only defence is that in the era (and area) in which I grew up, the teaching of Māori history was, to put it politely, minimal. Fortunately some self-study, through books like Vincent O’Malley’s The Great War for New Zealand, has since filled in the picture.

Equality of opportunity

I used to think this idea was a conservative subterfuge, deployed to downplay the need to tackle material poverty: “We need to focus on opportunities, not incomes!” Nowadays I agree that equality of opportunity is a core political goal. Lifting incomes remains essential, but as a means to something else – namely, enhancing individuals’ opportunities. After all, the government, whatever its policies and powers, can’t force people to live well; providing the foundation for those opportunities is all it can do. Of course, resources are still central to life chances. When rich and poor kids get such different upbringings, the latter are climbing the mountain of life wearing concrete overshoes. The data are unmistakeable: countries with smaller income imbalances have more equal opportunities. But that’s a subtler position than the one with which I started.

Having listed these changes, let me end with an uncertainty. As a researcher, I think a lot about the welfare system, on which there are two competing views.

The dominant one is that benefits should be conditional: in exchange for taxpayer support, people must do something, even if it just to look for paid work. In the other camp are the thinkers who argue benefits should be unconditional, given out as a mark of the recipient’s basic humanity and requiring nothing in return.

The latter argument appeals to powerful moral values; so too, however, does the conditional view. It embodies the reciprocity that sits at the heart of nearly all human relationships, even – I would argue – familial ones.

I go backwards and forwards on this question, and have reached no settled view. But so be it.

The poet John Keats praised something he called negative capability, the state “of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason”. Doubt is not a weakness but a strength. Without it, we would be locked in artificial certainty. And then we would have lost that most essential of human attributes, the capacity to change.

Stuff: The positive power of community connection

Our politics has strangely little to say about how people can lead better lives together.

Read the original on Stuff

If I told you that not being involved in a community group could be as bad for your health as becoming a smoker, you might think me deranged. But it’s true.

The insight stems from Robert Putnam’s classic American work Bowling Alone, which charted the decline of church groups, political parties, parent-teacher associations and even – as per the book’s title – bowling leagues. Because we are social animals, Putnam argued, our well-being relies heavily on positive, repeated contact with others. Community connections furnish emotional and financial support in tough times. Dwindling group membership thus spells bad news for people’s health.

Such facts seem relevant now, at the end of a strange year, as an increasingly divided New Zealand contemplates its frayed social fabric. February’s occupation of Parliament grounds has left a lingering disquiet and a sense that some people are splintering off from the rest of society – and indeed from the real world.

Research by the Helen Clark Foundation shows many New Zealanders are often lonely, especially the young and the poor. We are more atomised, too. Working from home, though a welcome revolution in many ways, has weakened office-based ties that were a major source of social connection.

Stronger communities could salve many of these wounds. Ironically, given the traditional distrust of the “mob mentality”, it is those with powerful community ties who are least likely to be picked off by dangerous, anti-democratic demagogues. Local bonds, whether tight or loose, can also fill in the gaps left by loneliness and help individuals find common ground.

It’s surprising, then, that mainstream politics has so little to say about community. If the word crops up in Jacinda Ardern’s speeches, for instance, it is as a token reference, shorn of real content.

Labour, supposedly the party of collective values, lacks a consistent vision for the life we might lead together, as opposed to what the party might do for individuals. Its Covid-fighting “team of five million” concept did useful work, but at a national not local level, and has in any case faded away in the post-lockdown era.

Yet most people, I think, thirst for a life that is rich in connections with others. By and large, they want to put down roots, know their neighbours, take part in community sports and festivals, and feel the growth of a dense web of bonds, ties and relations that can hold them in the warmth of others’ regard. These connections can be both a source of joy and a reservoir of strength.

While the decline of community life has probably been less precipitous here than in the US, we have still seen church, party and union membership dwindle under the influence of a market-based, hyper-individualised worldview. Nearly half of New Zealanders, official statistics show, have no supportive neighbours – even though that is overwhelmingly what they would like.

I see two main reasons why politics has failed to answer these needs. The first is the liberal fear that a community-promoting agenda might allow the many to dominate the one.

But the idea is not to force anyone into joining the local residents’ association against their will. If people want to stay home and watch Netflix, they can. The point is simply to enable community connection for those who want it.

The second obstacle is the belief that governments can’t create strong communities. And indeed they cannot. But they can lay the foundations.

Higher wages, for instance, would let people work fewer hours and take on more community commitments. Tougher regulation of the gig economy would give precarious workers more predictable shift patterns, helping them commit to coaching their children’s rugby team.

Greater security of tenure would allow renters to more confidently put down roots. Multigenerational housing would enable grandparents to live alongside grandchildren.

Such an agenda would respond to Māori ambitions to create communities oriented around whakapapa and manaakitanga. And it could be more broadly popular. Global polling shows people are happy to pay more tax for better public services – but they want the money spent locally.

The politics of community needn’t be hyper-partisan. The prime minister, who grew up in Morrinsville with a school-assistant mother and police-officer father, can speak convincingly about the virtue of small-town connections. But Chris Luxon can equally well testify to the solidarity that a religious community provides.

Either way, we need a positive vision for this politics – because it can also take on a darker hue. In the hands of the “trad wives” movement, for instance, it becomes a cover for a coercive, nostalgic vision, one based on supposedly ideal communities that in fact kept women and others firmly in their place.

Communities, after all, can oppress as well as support. So we need a politics that harnesses the latter, not the former. Because that desire for connection isn’t about to dissipate.

RNZ: Chief Ombudsman's OIA inquiry another pointer to govt's lack of transparency

The latest Open Government Partnership “action plan” does little to advance open government, and has few meaningful actions.

Read the original article on RNZ

Chief Ombudsman Peter Boshier's decision on Monday to investigate potential abuses of the Official Information Act (OIA) is yet another sign that all is not well when it comes to democracy in this country.

Boshier is concerned by journalists' claims that public agencies delay responding to their requests "as a bureaucratic tool to stifle the flow of information", and that when data is finally released, "it belongs in the history books rather than the headlines".

Journalists are not the only ones worried. Civil society groups are also up in arms at what they see as backsliding on transparency and openness.

For some of them, the latest straw has been the "national action plan" that ministers have put out for consultation until 12 December. The plan supposedly represents the commitment that Labour has made to the Open Government Partnership, a 77-country movement that requires member states to reduce secrecy, make themselves more accountable, and allow citizens to participate more deeply in their democracy.

As the name suggests, Open Government Partnership action plans are supposed to contain clear policies that will make a country's public processes profoundly more open. But our latest effort has been condemned by the New Zealand Council for Civil Liberties (NZCCL) as "yet another in a series of weak national action plans".

The most tangible commitments, such as setting up a register of the true owners of New Zealand companies, are initiatives that were underway already but "repackaged" for the action plan. Another initiative was described by the NZCCL as "so weak as to be a joke".

At every step of the way, individuals taking part in open-government workshops suggested meaningful commitments - then found they had been watered down. NGOs asked for the government to enforce basic standards for how it consults: for instance, minimum consultation periods and the publication of all submissions received.

Instead, public agencies will be required to use a "policy community engagement tool" that has no teeth or power to enforce standards.

At workshops, individuals suggested New Zealand adopt forums that have been used overseas to profoundly change citizens' control over democratic decisions: for instance, participatory budgeting, where residents discuss and allocate a portion of local council budgets, or citizens' assemblies, where a representative group of ordinary individuals meet to examine, debate and make policy on key public issues.

Instead, the government will "identify" examples of these forums, in order to "capture lessons learnt and share these to build capability". Since some councils are already experimenting with these methods, the action plan - bizarrely - puts the government behind the pace of change that is already happening, rather than leading it.

Civil society groups also asked for a review of the 80-plus secrecy clauses in legislation that override the right to information contained in the OIA, with a view to removing as many of these clauses as possible. Instead, ministers will tighten up the guidance for agencies that are looking to insert more such clauses.

The "open government" action plan, in short, actively envisages greater secrecy in future.

These failings are all the more galling given ministers' fabled commitment to running "the most open, most transparent government that New Zealand has ever had", in the words of former minister Clare Curran. While some improvements have been made, including the publication of ministers' diaries and a greater number of Cabinet papers, these hardly represent the transformation that Curran's words seemed to promise.

Journalists report that abuses of the OIA are as bad as ever, if not worse, while Minister Andrew Little's 2020 pre-election promise to review and improve the Act was later quietly dropped.

The one spot of good news is that the latest action plan has improved fractionally from earlier drafts, and now boasts a plan to ensure that those unable to access digital public services do not miss out, as well as a commitment to embed the charter that governs the controversial algorithms increasingly used by public agencies.

NGOs, many of them left feeling burnt by the process of developing the action plan, are still hoping it can be further strengthened, either during the current consultation or by adding new commitments next year. But after years of underwhelming plans developed under both National- and Labour-led governments, some remain cynical about the value of New Zealand's membership of the Open Government Partnership - as the NZCCL's press release makes clear.

"After four failed efforts to produce action plans that provide real benefits to the public from greater openness," it reads, "the council concludes that the New Zealand government is like a person who pays for their gym membership, but then wonders why their fitness doesn't improve when they don't actually do any exercise at the gym".

Spinoff: Campaigning on economic security sounds dull, but it might be Labour’s best option

It offers Labour a coherent story - but will it stick?

Read the original article on the Spinoff

I was once told, by someone who would know, that there are only two political campaigns: “time for change” and “don’t put it all at risk”. Every opposition campaign boils down to the former; every incumbent campaign, the latter.

Labour, as it looks towards a general election next year, has struggled to tell voters a convincing story about what they would be putting “at risk” if they switch to Christopher Luxon’s National. In recent months, though, a clear theme has begun to emerge: economic security. Delivering her party conference speech last month, Jacinda Ardern claimed that “the question” next year would be, “Who is best to help New Zealand navigate these tough times? Who can provide the security and certainty New Zealanders need?” In a recent newsletter to constituents, finance minister Grant Robertson wrote: “Our economic plan can be summed up in one sentence: to grow a high wage, low emissions economy that provides security in good and bad times.”

Compared to such rallying cries as “freedom” and “equal rights”, this appeal to economic stability can sound like dull stuff. But it has a strong pedigree in the Labour movement – and among reforming governments more generally.

For well over a century, New Zealanders have been acutely aware of the threat that economic instability poses to their well-being. Living in such a small country, buffeted by global economic winds like a rowboat in a thunderstorm, and possessing few organisations of any scale, we have often looked to the state to cushion economic shocks.

While the left tends to frame its past victories, including the world-leading introduction of tax-funded pensions in 1898, as triumphs of rights or equality, those achievements make just as much sense viewed through the lens of security. The first Labour government could hardly have made its intentions clearer when naming its landmark 1938 legislation the Social Security Act. Turning a patchwork of benefits into the foundations of a recognisably modern welfare state, and offering state support “from the cradle to the grave”, it was a direct response to the devastating economic precarity of the Great Depression.

Tapping a similar source of inspiration, one of the era’s leading intellectuals, the nation-building public servant Bill Sutch, titled his 1942 history The Quest for Security in New Zealand. Through an active state, the country had, Sutch argued, “do[ne] more in providing social and employment security than any other Western parliamentary democracy”. The historian W. H. Oliver, writing some decades later, described the growth of “a national social security consciousness … at two critical periods shortly prior to 1898 and 1938 when the country was recovering from, and still had memories of, very severe economic crises”.

Because the state is now far better at managing such crises, Covid has wreaked nothing like the havoc of the Great Depression or the little-remembered Long Depression of the 1880s and 90s. Nonetheless, Ardern and her team clearly spy a chance to tell a similar story: Labour brought you, the voter, safely through Covid, and can do so again; Luxon, with nothing similar on his resumé, represents a risk.

As an overarching theme, economic security has intuitive appeal. In a world wracked by war and menaced by climate change, it is clearly something voters crave. Rhetorically, it would unite otherwise disparate Labour achievements and plans – notably, Fair Pay Agreements and Social Insurance – into a coherent story about the state being there for families in tough times, preserving wages and guaranteeing peace of mind. It could also serve as an organising theme for other initiatives Labour might launch as it targets swing voters: policies to mitigate climate change, for instance, or boosts to early childhood education – a crucial element of parents’ return to the paid workforce and thus their economic security.

Potential pitfalls await, however. One Labour activist canvassing voters in the Hamilton West by-election says the mood is not one of gratitude for the government’s Covid stewardship but anger at still having to deal with the virus, despite all the sacrifices made. Much of the public felt secure during the pandemic, but that sensation may be a little like one’s virginity, irrecoverable once lost. The cost-of-living crisis, whoever is to blame, adds to a sense of instability.

To ensure the security theme resonated, Labour would have to stop committing political own goals and ruthlessly divest itself of off-message policies. Only then could it turn the spotlight onto National. Luxon has already demonstrated toughness by ditching his deeply unpopular policy of abolishing the 39% top tax rate. But for as long as he equivocates on his other policies – including tax breaks for landlords and property speculators – he will remain vulnerable to a “don’t put it all at risk” message. If his tax cuts, which would cost billions of dollars each year, remain on the table, Labour will argue that he can’t square things off just by cutting the examples of government “waste” National has identified: he’ll have to carve deeply into core services like health, education and welfare, or borrow more.

It’s open to Luxon, of course, to prove otherwise; but until he publishes a set of fully costed policies, Robertson will happily repeat the “Bermuda Triangle” attack that resonated at the last election: National can’t simultaneously maintain services, cut taxes and pay down debt, so its economic plans are fundamentally suspect.

Labour’s base would undoubtedly prefer a more activist and inspiring campaign than an appeal to security. But Robertson has signalled that budgets will be tight; meanwhile, public stimulus becomes harder to justify in times of high inflation, and – crucially – some of the government’s poorly targeted spending has left voters cynical about big-ticket, high-cost packages. Economic security isn’t sexy, but it might, to a Labour strategist, seem like the best option left.

Stuff: The jewellery tax ruse that gives people a free holiday

The New Zealand tax system has loopholes we should close – but we’ve done it before.

Read the original article in Stuff

I was in a Wellington jewellers yesterday, pretending to be interested in diamonds, when a shop assistant made an intriguing proposition. “We do offer a tax-free service,” she said.

I had, admittedly, solicited this response: I’d asked if it was true that, as friends had told me, one could avoid paying GST on jewellery – provided one was holidaying overseas.

The ruse, as described to me, takes advantage of the fact that GST isn’t levied on exports, as it’s designed to tax only those items consumed within the country. And for genuine exports, this makes sense.

But jewellers have found a clever, and enduring, loophole. Anyone heading away for a long weekend in Sydney, or a winter break in Bali, can pick up their ring or necklace “airside” – at, for instance, Auckland Airport’s Collection Point. Taking it overseas with them, and thus notionally “consuming” it outside the country, they need pay GST neither on pick-up nor – except in rare circumstances – on their return.

It is, if you do the sums, a nice little scheme. On a $4500 ring, the GST saved is $675, enough for a return flight to Sydney. On a $10,000 necklace, it’s $1500 – an airfare to Bali and back.

And, as it turns out, I needn’t have asked a sales assistant, because firms promote the loophole online. The Village Goldsmith tells customers they have to pay GST if they want to give a gemstone to their partner in New Zealand, but not if they do it overseas. The Diamond Shop says, cheerily, “Many of our customers take advantage of these tax savings, which help pay for their holidays. Can you think of a more romantic way to save money?”

Probably not – but I can think of fairer ones. Someone who scrimps and saves to buy their fiancée a present, but lacks the time or money to cover all the expenses of an overseas jaunt, will pay full price; a wealthy couple heading to the United States get 15% off and free flights. And in the latter case, the tax take is lower than it should be.

For all that, I don’t really blame people for using this loophole, especially when it’s perfectly legal and so widely advertised. It’s also very small fry in the greater scheme of things. I just think the loophole should be closed. And we can expect that it will be, since our tax authorities have a proud record of tackling far larger problems.

That, in fact, is much the most interesting story here. Many people fear that tax loopholes – especially the genuinely troubling ones that reap the hyper-wealthy millions of dollars – will always be with us. But not so. Holes in tax law are closed all the time.

Sometimes the schemes in question are clearly legal but shouldn’t be, so the law has to be changed. Sometimes it simply has to be enforced.

In 2009, the big four Australian-owned banks – ANZ, BNZ, ASB and Westpac – had to cough up $2.2b for having run so-called structured-finance transactions that created artificial “losses” to offset against their tax bill. The banks got absolutely monstered by Inland Revenue, and rightly so.

A few years later, two Christchurch-based orthopaedic surgeons, Ian Penny and Gary Hooper, were likewise found guilty of tax avoidance. They had, in essence, claimed that their income was corporate profit, which would have been taxed at 33%, rather than – as it actually was – personal income taxable at 39%.

The history of our tax system is, in short, a history of people thinking they’ve found ways to avoid paying their fair share, and then being trounced in court. While the authorities aren’t always successful, three out of every four cases is a victory, according to Inland Revenue. For each $1 spent on investigations, the agency finds $9.88 in evasion – surely one of the best investments in the history of government.

Such investigations remain necessary. Inland Revenue estimates New Zealand still loses at least $1.1b each year in evasion; the global Tax Justice Network thinks it could be as high as $7b. That would buy a lot of extra cancer drugs or new school buildings.

Consider, too, the business dealings of the Wright family, controversial Rich Listers who in 2015 “sold” their chain of childcare centres for $332m to a charity they control. The chain’s profits now go to the charity, untaxed, but are then sent to the Wrights as repayment for the “sale”.

Effectively the family will, until 2030, bank the profits, but without having to pay millions of dollars in tax they would otherwise owe.

Although this is eminently legal, experts like tax professor Craig Elliffe have questioned whether it’s an appropriate use of charitable status. It certainly looks to me like a loophole. And there’s no reason we couldn’t close it. After all, we’ve done that time and again.